Marcel Cuelenaere was a hero. This is his life story, as related to the Saskatoon Star Phoenix by his business partner, Dave Beaubier, another founding member of our firm.

Marcel Redmond Charles Cuelenaere was born at Leask on May 22, 1918. He was the youngest of three boys and one girl. His mother and father were both Belgian immigrants.

They owned and operated the Windsor Hotel in Leask. It was the only hotel in a small farm town which was then in the bush about 110 kilometers straight north of Saskatoon. French was spoken in the back of the hotel and English in the front. Marcel attended grade school and high school in Leask. In 1937, he entered the University of Saskatchewan. He joined the RCAF on March 3, 1941 after completing first-year law.

Marcel became a pilot. While he was training in Harvards in Saskatoon one sunny afternoon, he and another young pilot flew up to Leask. There they mock strafed the main street. With the engine roaring, they flew low down the main street of the little town, pulled up over the elevator, returned and made a second pass. When they landed back at their base in Saskatoon they were grounded for three days.

A woman in Leask had made a long-distance telephone call to the commanding officer in Saskatoon on the town’s party line and complained. She had guessed correctly that one of the young pilots was Marcel. He was still upset about that phone call when he related the story to me 40 years later.

In 1942, Marcel was shipped to Europe. He sailed there on one of the “Queens,” the Queen Mary or the Queen Elizabeth. The Queens carried troops to Europe without any escort. They were faster than the other ships and relied on their speed to avoid submarines. Once in England, Marcel was posted in a Royal Air Force squadron for Lancasters.

“In 1942, I was a boy of 10 living in Regina. Once each week I listened faithfully to the radio program “L for Lucky” about Lancaster bomber crews flying bombing raids.

In those programs we were winning. Our crews always came back from the air raids. No one was killed or maimed.

Overseas it was a different story. Tank crews and flyers usually bombed to death. Dr. Joe Schachter, a dentist, who went in as a first-aid man on D-Day and was in the front lines for 90 days after that, described the wounded to me years later with these words: “They weren’t wounded. They were mutilated. These young men and boys sacrificed themselves and performed frequent acts of heroism in situations that would freeze most of us in absolute terror. For most there was no memory or medal for their valour.”

Lancasters were the four-engined workhorses of RAF Bomber Command. Each had a crew of seven and carried 20,000 pounds of bombs. The life expectancy of a bomber crew in England at that time was 10 missions. Marcel began piloting his Lancaster on the famous RAF night bombing raids over Germany – Berlin, Essen and the Ruhr.

In June 1943, Marcel was flying on a night bombing raid over Hamburg. His Lancaster was “coned” at 20.000 feed. “Coning” occurred when one searchlight managed to follow his bomber. Once it was caught by the beam of light, other search lights “coned” in on it. The anti-aircraft fire from the ground batteries was concentrated on the coned plane.

Normally, that plan and its crew were blown from the sky and killed in a maelstrom of ack-ack and fire, falling pieces of falling aircraft and exploding shells and bombs in the black of night.

As soon as he was coned Marcel power dived his aircraft straight down through the night into his own bombs, the exploding bombs of the other aircraft, and the rising anti-aircraft fire. As the bomber was diving, its engines on full power, his rear gunner kept reporting over the intercom on the anti-aircraft fire: “They’re getting closer. They’re getting closer.”

When he finally began to pull back on the stick, Marcel had to get help from another crew member. The effort was so great that he feared that the plane’s control wires would break

He levelled off down at street level and flew the Lancaster down a flaming street towards Hamburg’s harbor as bombs fell around him and scattered shots were taken at the plane. He was so low that he was afraid that he would hit a ship in the harbor.

That night his Lancaster flew home “on the deck.” He was afraid to risk flying up through night fighters in an attempt to rejoin his squadron. It was a quiet crew as dawn appeared in the Eastern sky. They limped in low and landed at their base near Nottingham early that morning.

For that mission he was awarded his first Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) by King George VI in Buckingham Palace.

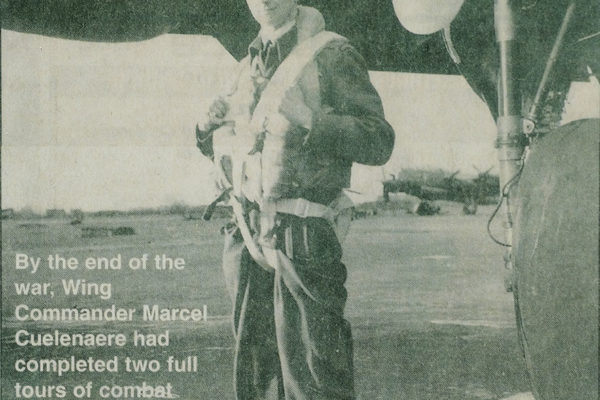

By D-Day – June 6, 1944 – Marcel had completed his first combat tour of 31 missions. He was in Canada as a decorated young hero when the invasion began. When he returned to England, he joined a group of precision RAF bomber crew who became known as the “Dam Busters.” By the time he began his second tour of duty, the Lancaster bomber had become a second skin to Marcel. Between bombing raids he instructed pilots in combat tactics and checked out aircraft and pilots. On one occasion, while evading enemy fighters in the course of an air raid, he piloted his Lancaster through a full 360-degree loop and didn’t know he’d done it until the crew told him about it back at the base.

Marcel flew a number of crippled Lancaster back from bombing missions. Most of them were shot up so badly that he couldn’t make it back to his home base. He and other pilots had a simple set of rules about where to land a damaged aircraft. First choice, a United States Army Air Force base; second choice, A Royal Canadian Air Force base; and third a Royal Air Force base. The ranking was according the quality of the food at each base. Inevitably the crew would be at the base for a few days while their plane was repaired and they are at the base mess.

Excerpt from the Star Phoenix, November 6, 1999.